Do parasites sometimes benefit humans?

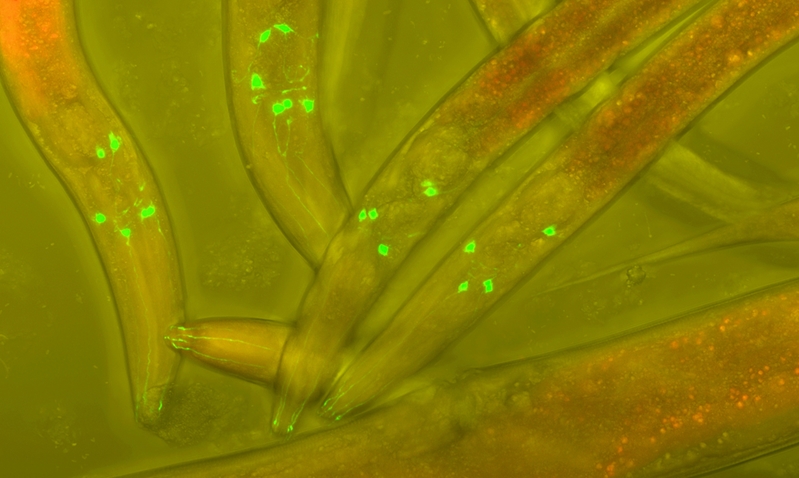

In November researchers for the Tsimane Health and Life History Project, a University of Mexico program for tracking the Bolivian indigenous group the Tsimane, discovered that helminths or parasitic roundworms may help women conceive, reported Stat. Roundworms prompt an anti-inflammatory response in humans. This reaction modulates the immune system and enables women with conception issues – problems normally attributed to overactive antibodies – to get pregnant.

For those familiar with similar studies, this wasn’t quite a revelation. Over the past decade, scientists have uncovered various uses for parasites, organisms most view as invasive and wholly harmful.

Changing parasitic perceptions

Scientists who study parasites are often amazed by their ability to manipulate the human body and its processes, reported The New York Times. These specialists assert that many scientists and lay people undervalue the parasite’s place in the global ecosystem.

“We’re trying to find elegant ways to spread the message that parasites are very important parts of ecosystems, and that any reasons for conserving any animal out there – from pandas to blue whales – also apply to parasites,” American Museum of Natural History ecologist Dr. Andres Gomez said in an interview with the newspaper.

This parasite-friendly outlook has spawned a variety of key studies. In 2012 researchers discovered that whipworms could regulate levels of intestinal bacteria in ailing mammals, reported Wired. The study, published in the journal PLoS, involved a test group of five rhesus monkeys with idiopathic chronic diarrhea. Researchers exposed the subjects to whipworms and found that four out of five recovered.

“Immune response is calibrated to the presence of worms. In their absence, you get a different response,” P’ng Loke, Ph.D., a microbiologist at New York University and the study’s lead researcher, explained.

Researchers like Loke postulate that humans and parasites developed in concert. In fact, they argue, parasites have always been essential to human life. “We’re not born with enough immune regulation; we rely on other organisms to get us to the right level, because they were always around,” science journalist Moises Velasquez-Manoff said.

Science supports this idea. Biologists have linked worm eradication to increases in autoimmune disease rates, reported the Anals of The New York Academy of Sciences.

The rise of worm therapy

Enterprising physicians and medical researchers have been working with live worms since the early 1990s, reported BBC. Around that time, gastroenterologist Dr. Joel Weinstock, now an instructor at Tufts University’s Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, hypothesized that increasing rates of inflammatory bowel disease could be attributed to rising hygiene levels – a result of worm eradication, among other things.

“Worms perform essential functions within the digestive system.”

Helminths regulate the internal processes of their hosts so they aren’t rejected. Weinstock reasoned that this regulatory technique not only helped the worms maintain residence but also eased human internal functions. Worms, he postulated, perform essential functions within the digestive system.

“Hygiene has made our lives better,” Weinstock said in an interview with The New York Times. “But in the process of eliminating exposure to the 10 or 20 things that can make us sick, we’re also eliminating exposure to things that make us well.”

To test his hypothesis, the gastroenterologist organized a number of experiments. Weinstock used worms to cure mice of asthma, multiple sclerosis and Type 1 diabetes. In 2005 he tested his theory on a group of 29 pig farmers who suffered from the gastrointestinal condition Crohn’s disease. The participants ingested trichuris suis, a pig whipworm. Approximately 21 of the test subjects went into remission.

According to Scientific American, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has since classified trichuris suis as an Investigational New Drug.