How killer T cells control Zika infection

Zika, a virus transmitted primarily by Aedes mosquitoes, became a significant global health concern last year. The threat emerged in Brazil and quickly spread to other parts of the world, causing microencephaly and other birth defects in babies born to infected mothers, as well as rare neurological conditions in adults. Although Zika has faded from the news as the outbreak subsides, many critical questions remain, including:

- Why does the virus remain in certain tissues after the systemic infection has dissipated?

- How does the immune system fight the virus?

- How does the body protect against reinfection?

- What determines the potential for long-term complications?

To help address some of these questions, researchers at the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology explored how CD8+ T cells affect Zika virus infection. CD8+ T cells, often called cytotoxic or killer T cells, are immune system components known to destroy cancerous, virus-infected and other damaged cells. The researchers’ findings, published in January in Cell Host & Microbe, provide evidence that CD8+ T cells serve as important gatekeepers that control Zika infection or limit the severity of disease. The study also provides an important tool to track Zika-specific T cells in the context of different disease models.

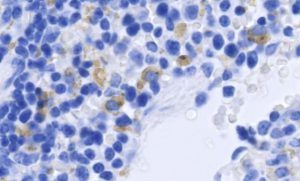

Mouse spleen cells infected with Zika virus. Infected cells are shown in brown, cell nuclei in blue. Image: Courtesy of the Shresta lab at La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology.

“Our study acknowledges the importance of T cells in an environment where most people are focused on antibodies,” the study’s senior author, Dr. Sujan Shresta, said in a press release. “For most diseases a strong antibody response is enough. But with Zika and dengue viruses a phenomenon known as antibody-dependent enhancement is a concern, which makes a strong T cell response really important.”

Previous research suggested that T cells play a key role during dengue infection, leading Shresta and her team to wonder whether this was the case for Zika. In the new study, the researchers used antibodies to block the receptor for interferon 1 (IFNAR), causing mice to become susceptible to infection with Zika virus. They then isolated T cells from Zika-infected mice and mapped which portions of the virus resulted in a strong immune response.

The experiments were then replicated in T cell-competent mice, which also mounted a strong CD8+ T cell response to Zika infection. Thus, the team created a new mouse model for Zika that can be used for studying Zika-specific T cell responses, as well as testing vaccines and antiviral treatments.

“Being able to track Zika-specific T cells across different model systems provides a valuable tool to better understand sexual and trans-placental transmission and how the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and reaches other immune-privileged areas such as testes and the eye,” first author Dr. Annie Elong Ngono said.

Do you work in this area of research? We offer a variety of related reagents for studying virology and immunology, including: