An unexpected connection between cancer metastasis and autism

An international team of researchers, led by Dr. Johanna Ivaska of the Turku Centre for Biotechnology, has found that breast cancer cell metastasis can be prevented by the SHANK protein. Previously, SHANK had only been studied in the central nervous system; it’s mainly known for its link to autism. The new study was published in March in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

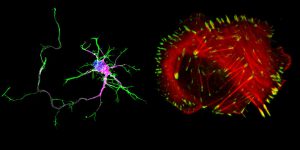

SHANK regulates adhesion and protrusion in very different cell types: cancer cells and neurons. This image, taken by Dr. Guillaume Jacquemet, reveals the distinct morphologies of neurons and cancer cells. On the right: a primary rat hippocampal neuron stained for actin (green), DAPI (blue) and MAP2 (purple). On the left: a bone cancer cell stained for actin (red) and paxillin (green). Photo credit: Turku Centre for Biotechnology.

The research team was using large-scale screens to pinpoint new genes involved in cancer cell metastasis. Their work demonstrated that SHANK prevents cancer cells’ ability to adhere, migrate and invade surrounding tissue. Mutations in the SHANK protein impaired its ability to prevent adherence of both breast cancer cells and neurons.

The team then explored the mechanism behind this finding. After solving the three-dimensional structure of the SHANK protein, they conducted cell culture experiments and found that SHANK limits the ability of a protein called Rap1 to activate integrins, or cell adhesion receptors. This process regulated cancer cell motility as well as the morphology and branching of neurites, which are critical for normal brain function.

“The same factors can regulate cell shape and adhesion in very different cell types,” lead author Dr. Ivaska said in a press release. “Our results revealed that gene mutations in SHANK, found in autistic patients, impair SHANK’s ability to prevent the adherence of both neurons and breast cancer cells. This once again demonstrates the power of basic research in facilitating our understanding of several human diseases.”

The research team is now exploring whether SHANK proteins have other impacts on cancer cells, including their proliferation. If you work in this area of research, you might be interested in one of our related products for studying neurobiology and cancer, including integrin antibodies from the laboratory of Dr. Richard H. Aster at the Blood Center of Wisconsin.