Recent advances in tissue generation

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have created a new technique for developing tissue via human stem cells, reported MIT News. The methodology, detailed in a study published in the journal Nature Communications, involves programming human stem cells to produce transplantable tissue on demand.

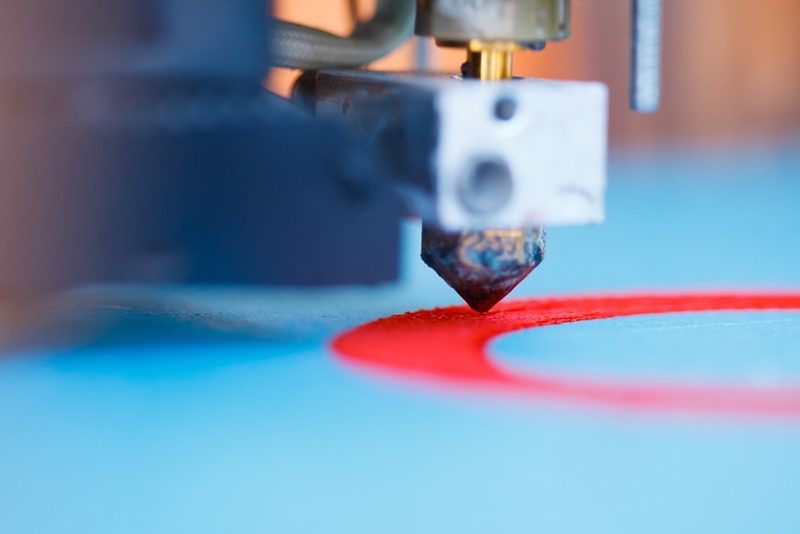

Over the past decade, biomedical researchers have made major strides in the field of tissue engineering. This recent MIT study demonstrates just how quickly tissue engineering technology is evolving. From 3-D printers to stem cells, researchers are exploring a variety of tissue-production tools in an effort to make organ transplantation a thing of the past.

Printing out the future

The 3-D printing frenzy has enveloped a number of industries, including health care. In February of 2014, Jennifer Lewis, Sc.D., a materials scientist at Harvard University, created an organic protein matrix embedded with living cells using a custom 3-D printer, reported The New Yorker. Lewis and her team then created a network of vessels within protein matrix. These vessels supplied nutrients to cells and transformed the matrix into a self-sustaining swath of living tissue.

“It’s a bio-inspired approach to creating materials that can heal themselves,” Lewis said in an interview with the magazine. “My big role in the project was to find ways to use 3-D printing to embed this microvascular network. Once we did that, it was pretty easy for me to see the broader implications.”

Lewis isn’t alone. Dr. Darryl D’Lima, director of the Shiley Center for Orthopaedic Research and Education at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, used a 3-D printer to create cartilage, reported The New York Times. And, according to CNN, others have printed transplantable tracheas and artificial ears.

With each of these developments, researchers get closer to their ultimate goal: printing whole functioning organs.

“The grand challenge is to make a whole kidney – that is our moon shot,” Lewis said. “We see this as a ladder, one step following the next. Creating just a single nephron would be a great achievement. But there are a million in each kidney.”

Animal meets man

Three research farms in the U.S. are attempting to grow human tissue within the bodies of animals, reported the MIT Technology Review. This process, which involves injecting human stem cells into pig and sheep embryos, produces human-animal hybrids, or chimeras. Using this technique, researchers hope to produce tissues that would comport with the bodies of human patients needing transplants.

This tissue-production technique is rather controversial. In September of last year, the National Institutes of Health said it would stop funding research using chimeras. Many biomedical researchers agreed with the NIH’s decision, reported NPR.

“Researchers hope to produce tissues that would comport with the bodies of human patients needing transplants.”

“The special issue here with stem cells is that those types of human cells are so powerful and so elastic that there’s great worry about the degree to which the animals could become humanized,” bioethicist Insoo Hyun said in an interview with the news organization.

Proponents of this tissue-production method believe it could revolutionize medicine and save thousands of lives.

“This could have a big impact in the way medicine is practiced,” Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Ph.D., a professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and key figure in stem cell research, told NPR. “We don’t have enough organs for transplantation. Every 30 seconds of every day that passes, there is a person that dies that could be cured by using tissues or organs for transplantation.”

According to the journal Science, Belmonte was in line to receive The Pioneer Award, a $500,000 research grant sponsored by the NIH, before the controversy surrounding human-animal chimeras picked up steam. Ultimately, the organization chose not to award him the prize.

However, Belmonte’s groundbreaking work has forced the NIH to reconsider its position on the intriguing technique. In November, it hosted an ethics workshop on such research. Advocates hope the technique will gain wider legitimacy within the biomedical research community but before that can happen, the NIH must lift its moratorium.

“We believe human/non-human chimerism studies in pre-gastrulation embryos hold tremendous potential,” a group of Stanford University researchers said in an open letter to the organization. “Given that the objective of the NIH is to enable discoveries that advance human health, the restrictions presented serve to impede scientific progress in regenerative medicine and should be lifted.”